- Home

- Campbell, Ramsey

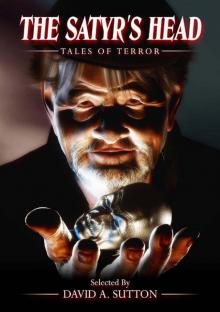

The Satyr's Head: Tales of Terror

The Satyr's Head: Tales of Terror Read online

The Satyr’s Head

Tales of Terror

Selected by David A. Sutton

The Satyr’s Head: Tales of Terror

First published as The Satyr’s Head & Other Tales of Terror

by Corgi Books 1975

This edition © 2012 by David A. Sutton

Cover artwork & design © 2012 by Steve Upham

The Nightingale Floors © 1975 by James Wade

The Previous Tenant © 1975 by Ramsey Campbell

The Night Fisherman © 1975 by Martin I. Ricketts

Sugar and Spice and All Things Nice © 1975 by David A. Sutton

Provisioning © 1975 by David Campton

Perfect Lady © 1975 by Robin Smyth

The Business About Fred © 1975 by Joseph Payne Brennan

Aunt Hester © 1975 by Brian Lumley

A Pentagram for Cenaide © 1975 by Eddy C. Bertin

The Satyr’s Head © 1975 by David A. Riley

The editor and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the copyright material in this book. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions in the above list and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced , stored in a retrieval system, rebound or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author and publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978-0-9539032-3-8

Shadow Publishing, 194 Station Road, Kings Heath,

Birmingham, B14 7TE, UK

[email protected]

http://davidasutton.co.uk

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to

- Mike Ashley -

- Charles Black -

- Steve Upham -

Contents

INTRODUCTION

THE NIGHTINGALE FLOORS by James Wade

THE PREVIOUS TENANT by Ramsey Campbell

THE NIGHT FISHERMAN by Martin I. Ricketts

SUGAR AND SPICE AND ALL THINGS NICE by David A. Sutton

PROVISIONING by David Campton

PERFECT LADY by Robin Smyth

THE BUSINESS ABOUT FRED by Joseph Payne Brennan

AUNT HESTER by Brian Lumley

A PENTAGRAM FOR CENAIDE by Eddy C. Bertin

THE SATYR’S HEAD by David A. Riley

INTRODUCTION

DURING THE EARLY part of the 1970s I had begun editing and producing my fanzine Shadow: Fantasy Literature Review. This was in response to the numerous horror and fantasy fanzines then being devoted to film. And there was a lot happening on the literary side. The Pan Book of Horror Stories was in its middle age. The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series had emerged in the mid-sixties, reprinting many classic works and later contemporary fantasy writers. Arkham House, having recently published Thirty Years of Arkham House in 1969, was to enter its most productive two decades, with something like seventy-plus titles from both contemporary, classic and “pulp” writers. Many paperback anthologies edited by August Derleth, Peter Haining and numerous others were popping up. The UK paperback publishers were all keen to have a horror genre line, thus Pan, Panther, Four Square, Sphere, Corgi, Fontana, Tandem, and so on all were bringing out horror series or one-off anthologies.

One of the paperback houses, Sphere Books, contacted me after seeing and being impressed with the copies of Shadow FantasyLiterature Review I had sent them. Their editor, Anthony Cheetham, commissioned me to edit a series of annual anthologies called New Writings in Horror & the Supernatural, exclusively to bring out previously unpublished tales of horror by new and well-known genre writers. On the other side of the coin, Sphere hired Richard Davis to edit the Year’s Best Horror Stories series. Alas, Sphere backed away from New Writings after two volumes. Year’s Best fared a little better, but was eventually dropped by Sphere. (Luckily it was continued by Daw Books in the USA under editors Gerald W. Page from volume four and Karl Edward Wagner from volume eight). In 1972 I was busy compiling the contents for New Writings volume three when the expected contract failed to materialise…

With a batch of stories already to hand, I then contacted Corgi Books, a division of Transworld Publishers, and pitched to them a one-off anthology called The Satyr’s Head & Other Tales of Terror. They liked the concept and the book was duly published in 1975 and quickly went out of print. Now, nearly forty years later here is The Satyr’s Head: Tales of Terror, a new incarnation for a new generation of horror readers!

David A. Sutton

January 2012

THE NIGHTINGALE FLOORS by James Wade

I

START TALKING ABOUT a broken-down old museum (one of those private collections set up years ago under endowments by some batty rich guy with pack-rat instincts) where strange things are supposed to happen sometimes at night, and people think you’re describing the latest Vincent Price horror movie, or the plot of some corny Fu Manchu thriller, the kind that sophisticates these days call “campy” and cultivate for laughs.

But there are such places, dozens altogether I guess, scattered around the country; and you do hear some pretty peculiar reports about some of them once in a while.

The one I knew was on the South Side of Chicago. They tore it down a few years ago during that big urban renewal project around the university—got lawyers to find loopholes in the bequest, probably, and scattered the exhibits among similar places that would accept such junk.

Anyway, it’s gone now, so I don’t suppose there’s any harm in mentioning the thing that went on at the Ehlers Museum in the middle 1950’s. I was there, I experienced it; but how good a witness I am I’ll leave up to you. There’s plenty of reason for me to doubt my own senses, as you’ll see when I get on with the story.

1 don’t mean to imply that everything in the Ehlers Museum was junk—far from it. There were good pieces in the armour collection, I’m told, and a few mummies in fair shape. The Remingtons were focus of an unusual gathering of early Wild West art, though some of them were said to be copies; I suppose even the stacks of quaint old posters had historical value in that particular field. It was because everything was so jammed together, so dusty, so musty, so badly lit and poorly displayed that the overall impression was simply that of some hereditary kleptomaniac’s attic.

I learned about the good specimens after I went to work at the museum; but even at the beginning, the place held an odd fascination for me, trashy as it might have appeared to most casual visitors.

I first saw the Ehlers Museum one cloudy fall afternoon when I was wandering the streets of the South Side for lack of something better to do. I was still in my twenties then, had just dropped out of the university (about the fifth college I failed to graduate from) and was starting to think seriously about where to go from there.

You see, I had a problem—to be more accurate, I had a Habit. Not a major Habit, but one that had been showing signs lately of getting bigger.

I was one of those guys people call lucky, with enough money in trust funds from overindulgent grandparents to see me through life without too much worry, or so it seemed. My parents lived in a small town in an isolated part of the country, where my father ran th

e family industry; no matter to this story where or what it was.

I took off from there early to see what war and famine had left of the world. Nobody could stop me, since my money was my own as soon as I was twenty-one. I didn’t have the vaguest notion what I wanted to do with myself, and that’s probably why I found myself a Korean War veteran in Chicago at twenty-six with a medium-size monkey on my back, picked up at those genteel campus pot parties that were just getting popular then among the more advanced self-proclaimed sophisticates.

Lucky? I was an Horatio Alger story in reverse.

You see, although my habit was modest, my income was modest too, with the inflation of the forties and fifties eating into it. I had just come to the conclusion that I was going to have to get a job of some kind to keep my monkey and me both adequately nourished.

So there I was, walking the South Side slums through pale piles of fallen poplar leaves, and trying to figure out what to do, when I came across the Ehlers Museum, just like Childe Roland blundering upon the Dark Tower. There was a glass-covered signboard outside, the kind you see in front of churches, giving the name of the place and its hours of operation; and someone had stuck a hand-lettered paper notice on the glass that proclaimed, “Night Watchman Wanted. Inquire Within”.

I looked up to see what kind of place this museum-in-a-slum might be. Across a mangy, weed-cluttered yard I saw a house that was old and big—even older and bigger than the neighbouring grey stone residences that used to be fashionable but now were split up into cramped tenement apartments. The museum was built of dull red brick, two and a half stories topped by a steep, dark shingled roof. Out back stood some sort of addition that looked like it used to be a carriage house, connected to the main building by a covered, tunnel-like walkway at the second storey level, something like a medieval drawbridge. I found out later that I was right in assuming that the place had once been the private mansion of Old Man Ehlers himself, who left his house and money and pack-rat collections in trust to preserve his name and civic Fame when he died, back in the late twenties. The neighborhood must have been fairly ritzy then.

The whole place looked deserted: no lights showed, though the day was dismally grey, and the visible windows were mostly blocked by that fancy art-nouveau stained glass that made Edwardian houses resemble funeral parlors. I stood and watched a while, but nobody went in or out, and I couldn’t hear anything except the faint rattle of dry leaves among the branches of the big trees surrounding the place.

However, according to the sign, the museum should be open. I was curious, bored, and needed a job: no reason not to go in and at least look around. I walked up to the heavy, panelled door, suppressed an impulse to knock, and sidled my way inside.

“Dauntless, the slug-horn to my lips I set…”

II

The foyer was dark, but beyond a high archway just to the right I saw a big, lofty room lit by a few brass wall fixtures with gilt-lined black shades that made the place seem even more like a mortuary than it had from outside. This gallery must once have been the house’s main living room, or maybe even a ballroom. Now it was full of tall, dark mahogany cases, glass-fronted, in which you could dimly glimpse a bunch of unidentifiable potsherds, stuck around with little descriptive placards.

The walls, here and all over the museum, were covered with dark red brocaded silk hangings or velvety maroon embossed wallpaper, both flaunting a design in a sort of fleur-de-lys pattern that I later learned was a coat of arms old Ehlers had dug up for himself, or had faked, somewhere in Europe.

The building looked, and smelled, as if nobody bad been there for decades. However, just under the arch stood a shabby bulletin board that spelled out a welcome for visitors in big alphabet-soup letters, and also contained a photo of the pudgy, mutton-chop bearded founder, along with a typed history of the museum and a rack of little folders that seemed to be guide-catalogues. I took one of these and, ignoring the rest of the notices, walked on into the first gallery.

The quiet was shy-making; for the first time in years, I missed Muzak. My footsteps, though I found myself almost tiptoeing, elicited sharp creaks from the shrunken floorboards, just as happens in the corridors of the Shogun’s old palace at Kyoto, which I visited on leave during the Korean War. The Japs called those “Nightingale Floors”, and claimed they had been installed that way especially to give away the nocturnal presence of eavesdroppers or assassins. The sound was supposed to resemble the chirping of birds, though I could never see that part of it.

I wondered what the reason was for Old Man Ehlers to have this kind of flooring. Just shrinkage of the wood from age, maybe. But then, he’d been around the world a lot in his quest for curios, probably. Maybe the idea for the floor really was copied from the Shogun’s palace. But if so, why bother, since it wasn’t the sort of relic that could be exhibited?

Anyway, I walked through that gallery without giving the specimens more than a glance. I understand that the Ehlers Collection of North American Indian pottery rates several footnotes in most archaeological studies of the subject, but for myself I could never understand why beat-up old ceramic scraps should interest anybody but professors with lots of time on their hands and no healthy outlets for their energy. (Maybe that attitude explains my never graduating from college, or why I picked up a habit instead of a Hobby; or both.)

The next gallery was visible through another arch, at right angles to the first. Even after I had looked over the floor plan of the museum, and learned to make my way around in it somehow, I never really understood why one room or corridor connected with another at just the angle and in just the direction that it indisputably did. On this first visit, I didn’t even try to figure it out.

The second gallery was more interesting: armour and medieval armaments, most impressive under that dull brazen light and against that wine-dark wallpaper and hangings. I kept walking, but my attention had been tweaked.

The third room, a long and narrow one, held most of the Remington cowboy scenes, and a few sculptural casts of the Dying Gladiator school. For some reason, this was the darkest gallery in the whole place—you could hardly see to keep your footing; but the squeaky floor gave you a sort of sonar sense of the walls and furnishings, as if you were a bat or a dolphin or a blind man.

After that came the framed posters from World War I (“Uncle Sam Wants YOU!”) and the 19th century stage placards, well lit by individual lamps attached to their frames, though some of the bulbs had burned out. Next was a big, drafty central rotunda set about tastefully with cannon from Cortez’ conquests and a silver gilt grand piano, decorated with Fragonard cupids, which Liszt once played, or made a girl on top of, or something.

All this time no sight of a human being, nor any sound except the creaking floorboards under my feet. I was beginning to wonder whether the museum staff only came out of the woodwork after sunset.

But when I had made my way up a sagging ebon staircase to the second floor, and poked my nose into a narrow, boxlike hallway with small, bleary windows on both sides (which I figured must be the covered drawbridge to the donjon keep I’d glimpsed from outside), I did finally hear some tentative echoes of presumably human activity. What kind of activity it was hard to say, though.

First of all, it seemed a sort of distant, echoing mumble, like a giant groaning in his sleep. Granted the peculiar acoustics here, I could put this down to someone talking to himself—not hard to imagine, if he worked in this place. Next, from ahead, I caught further creaking, coming from the annex, that was analogous to the racket I had been stirring up myself all along from those Nightingale Floors. The sound advanced and I was almost startled when the thoroughly prosaic figure responsible hove into view at the end of the corridor—startled either because he was so prosaic, or because it didn’t seem right to meet any living, corporeal being in these surroundings; I couldn’t figure out which.

This old fellow was staff, all right: his casual shuffle and at-home attitude proclaimed it, even if he hadn’t been wear

ing a shiny blue uniform and cap that looked as if they’d been salvaged from some home for retired streetcar motormen.

‘I saw the sign outside,’ I said to the old man as he approached, without preliminaries, and rather to my own surprise. ‘Do you still have that night watchman job open?’

He looked me over carefully, eyes sharply assessing in that faded, wrinkled mask of age; then motioned me silently to follow him back along the corridor to the keep and into the dilapidated, unutterably cluttered, smelly office from which, I learned, he operated as Day Custodian.

That was how I went to work for the Ehlers Museum.

III

My elderly friend, whose name was Mr. Worthington, himself comprised all the day staff there was, just as I constituted the entire night staff. A pair of cleaning ladies came in three days a week to wage an unsuccessful war against dust and mildew, and a furnace man shared the night watch in winter; that was all. There was no longer a curator in residence, and the board of directors (all busy elderly men with little time to spend on the museum) were already seeking new homes for the collections, anticipating the rumored demolition of the neighbourhood.

In effect, the place was almost closed now, though an occasional serious specialist or twittery ladies’ club group came through; like as not rubbing shoulders with snot-nosed slum school kids on an outing, or some derelict drunk come in to get out of the cold, or heat.

Worthington told me all this, and also the salary for the night job, which wasn’t high because they had established the custom of hiring university students. I made a rapid mental calculation and determined that this amount would feed me, while my quarterly annuity payments went mostly to the monkey. So I told Worthington yes. He said something about references and bonding, but somehow we never actually got around to that.

The Satyr's Head: Tales of Terror

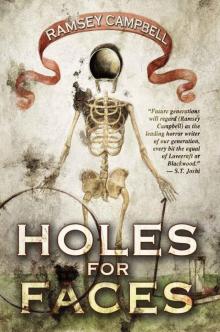

The Satyr's Head: Tales of Terror Holes for Faces

Holes for Faces